Historical work on spiritualism involves tracking peripatetic lecturers and spiritualist mediums and missionaries through their active years during the second half of the nineteenth century. These directories can make that easier.

They also provide other riches apart from strictly spiritualist ones. The Progressive Annuals published by Jackson Davis from 1862-64, for example, give lists of Anti-Slavery and Temperance lecturers, lists of practicing women physicians, and lists of women who were wearing bloomers in public (“Dress Reformers”). James Peebles and Hudson Tuttle in their Year-Book of Spiritualism in 1871, include lists of spiritualists, progressives, and other reformers from Europe.

Finding these directories was a chore. For their help, I thank the staffs of the Library of Congress, the American Antiquarian Society, the Boston Public Library, the Green Library at Stanford University, the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, the Van Pelt Library at the University of Pennsylvania, the Andover-Harvard Theological Library and the Lamont Library at Harvard University.

Finding these directories was a chore. For their help, I thank the staffs of the Library of Congress, the American Antiquarian Society, the Boston Public Library, the Green Library at Stanford University, the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, the Van Pelt Library at the University of Pennsylvania, the Andover-Harvard Theological Library and the Lamont Library at Harvard University.

Entering the lists into the computer and proofreading them was another chore. These are not exact reproductions of the original lists. I have modified them in a few ways. First, I have re-formatted them to be web-friendly. Second, I have corrected obvious typographical errors. I noticed, for example, when entering Clark’s Spiritualist Registers, that either he or his typesetter sometimes reversed the initials of people’s first names. When I have been certain that they have been reversed, I have corrected them. I have not filled them out, however, with their full names: for example, “A. J. Davis” remains precisely that, instead of “Andrew Jackson Davis.” Nevertheless, in order to make these lists more responsive to search engines, I have expanded the abbreviations of first names into their full form, so that, for example, “Geo.” has become “George,” and “Jas.” has become “James.” The same for “Wm.,” “Chas.,” “Benj.,” “Jos.,” “Jno.,” “Eliz.,” and so on. Nicknames and diminutives, however, such as “Lottie” instead of “Charlotte,” and “Lizzie” instead of “Elizabeth,” have remained as they appeared in the originals. A few people seem to have used, or at least tolerated, different spellings of their names in various sources. At the expense of consistency, I have left them as they appeared in each listing or citation. Examples are Semantha (var. Samantha) Mettler (var. Metler), Daniel Goddard (var. Godard), Eliza Kenny (var. Kenney), and Isaac Rehn (var. Rhen).

I have been selective about the content I have drawn from the original sources. I have not included the full texts of the Spiritualist Registers, the Progressive Annuals, and the Year-Book of Spiritualism. I have been most interested in providing lists of lecturers, mediums, reformers, organizations, publications, and association members. I have included some other portions of the texts, such as brief essays on spiritualist philosophy or history, although I cannot say exactly why I was more inclined to include one item rather than another.

The lists are snapshots of the leadership of the spiritualist movement. As the original compilers were well aware, they are imperfect documents. Spiritualism began in the later 1840s, but it took a few years to develop into a coherent movement, complete with leaders, common practices and doctrines, meeting places, associations, and established lecture circuits. Only after these fell into place was it possible to compile lists for various purposes. Even so, the huge majority of spiritualists and mediums never appeared in any list. Uriah Clark believed there were easily ten times the number of mediums in the United States as he was able to list. There was a large social price to pay for becoming publicly known as a committed spiritualist. In addition, spiritualism appealed particularly to people who were of independent minds. They were not well-known for being able to form strong and stable associations and organizations, and many of them were loathe to try, in any case. And finally, people who appeared on lists were generally the leaders of the movement, not the large mass of followers of varying degrees of commitment and faith, many of whom drifted in and out of the movement.

The lists are snapshots of the leadership of the spiritualist movement. As the original compilers were well aware, they are imperfect documents. Spiritualism began in the later 1840s, but it took a few years to develop into a coherent movement, complete with leaders, common practices and doctrines, meeting places, associations, and established lecture circuits. Only after these fell into place was it possible to compile lists for various purposes. Even so, the huge majority of spiritualists and mediums never appeared in any list. Uriah Clark believed there were easily ten times the number of mediums in the United States as he was able to list. There was a large social price to pay for becoming publicly known as a committed spiritualist. In addition, spiritualism appealed particularly to people who were of independent minds. They were not well-known for being able to form strong and stable associations and organizations, and many of them were loathe to try, in any case. And finally, people who appeared on lists were generally the leaders of the movement, not the large mass of followers of varying degrees of commitment and faith, many of whom drifted in and out of the movement.

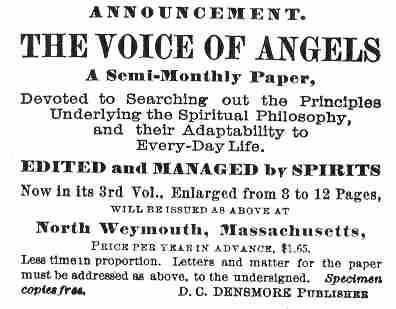

Each of the authors of these lists was composing a list for his or her own purposes. The weekly lists of spiritualist lecturers in the Banner of Light, for example, functioned as free national bulletin boards for people to advertise themselves as traveling lecturers or mediums. The advertising motive is less pronounced in some of the other directories and lists. John Bundy, as editor of the Religio-Philosophical Journal, made some effort to exclude from his paper’s listings mediums whom he believed were fraudulent. Luther Colby, editor of the Banner of Light, made little effort to do so. On the other hand, Victoria Woodhull’s perfunctory lists of lecturers in Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly seem merely like efforts to demonstrate to a skeptical readership that others, too, believed in what she called “social freedom.”

Adaline Buffum Determines to Publish News from the Spirit World

The lists of the Massachusetts Spiritualists’ Association functioned as a public record of its activities and membership, an announcement of dues paid and unpaid, and a record of those who attended the Association’s annual convention. They resemble the lists that William Lloyd Garrison published in the Liberator of the contributions received at the annual meetings of the Massachusetts and New-England Anti-Slavery Societies. Some lists of names essentially add weight and seriousness to declarations or manifestos, such as that of the New-England Spiritualists’ Association or the Society for the Diffusion of Spiritual Knowledge.

Uriah Clark had been a Universalist minister before the denomination disenfranchised him for his spiritualist activities. His Spiritualist Registers resemble in form and intent the annual Universalist Registers that Aaron Grosh published in Utica, beginning in 1839. The Spiritualist Registers not only highlighted the leaders of the movement, analogous to the clerical listings in the Universalist Registers, but also, one might say, reserved for spiritualism a place among other denominations, just as Universalism had been concerned to do for itself in its earlier, more fluid days. Clark’s Spiritualist Registers also functioned as promotional pieces for the movement, analogous to the religious tracts of other denominations.

The listings only concern themselves with the nineteenth century. For similar listings of the next generations of spiritualists, psychics, occultists, etc., see [William C.] Hartmann’s Who’s Who in Occult, Psychic and Spiritual Realms in the United States and Foreign Countries (Jamaica, NY, 1925) and Hartmann’s International Directory of Psychic Science and Spiritualism (Jamaica, NY, 1930). Later still is Hans Holzer’s The Directory of the Occult (Chicago, 1974), The International Psychic Register (Erie, PA, 1977), Who’s Who in the Psychic World (Phoenix, AZ, n.d.), Howard Rodway, The Psychic Directory (London, 1984), and Miriam C. Larsen, Where Are the Psychics? (Garland, TX, 1985). Current list of spiritualists and spiritualist organizations:

Crumbaugh Spiritualist Church, World Directory of Spiritualist Churches.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::