Elevating the Race

Members of other new religions of the early- and mid-nineteenth century—Mormons, Oneida Perfectionists, Shakers—were dissatisfied with the way human sexual relations were handled in the world. Spiritualists, too, had a vision that would direct sexual relations toward a more heavenly or angelic end.

1. The Root of All Reform

Sexual relations, it was believed, formed a kind of electrical circuit, joining the negative and positive “magnetic” energies of the man and woman. And each person was a storage battery of energy, which had to be full in order to convey a healthy charge that would result in a healthy child. Thus, activities that would drain the battery—especially weakening or short-circuiting its charge—were believed to be unhealthy, such as frequent sex that led to the male’s seminal emission, or any kind of masturbation. Sexual relations without ejaculation or climax, however, charged the battery, and, like physical exercise, could strengthen the organism.

As early as 1842, the influential phrenologist Orson Squire Fowler, who, together with his brother Lorenzo Niles Fowler, headed a publishing company for progressive publications, wrote that the root of all reform was “social reform.” Every other reform movement—Abolitionism, woman’s rights, and so on—was simply directing its efforts at pruning the outermost branches of human society. The “marriage reform,” however—the reorganization of sexual relations—took the axe to the root of the problem. If superior humans could be bred, the need for other reforms would disappear, because moral progress would occur naturally, through the progressive expression of humans’ newly-elevated nature. Evolution and forward change in human society was possible. “Man creates man” was the motto of this view, whose adherents pitted themselves against a traditional religious view that accepted human society, nature, and destiny, as static, predetermined, and divinely ordained (“God creates man”).

As early as 1842, the influential phrenologist Orson Squire Fowler, who, together with his brother Lorenzo Niles Fowler, headed a publishing company for progressive publications, wrote that the root of all reform was “social reform.” Every other reform movement—Abolitionism, woman’s rights, and so on—was simply directing its efforts at pruning the outermost branches of human society. The “marriage reform,” however—the reorganization of sexual relations—took the axe to the root of the problem. If superior humans could be bred, the need for other reforms would disappear, because moral progress would occur naturally, through the progressive expression of humans’ newly-elevated nature. Evolution and forward change in human society was possible. “Man creates man” was the motto of this view, whose adherents pitted themselves against a traditional religious view that accepted human society, nature, and destiny, as static, predetermined, and divinely ordained (“God creates man”).

This was a “progressive” view of human reproduction. It was “evolutionist,” but in a pre-Darwinian and Larmarckian sense. The biology of inheritance was not understood: Offspring could inherit the characteristics acquired by the parents, including such things as intellectual learning, or moral or spiritual development.

Breed the Lessons in the Bones

The susceptibility of the fetus to temporary, impressed, mental or spiritual characteristics was thought to occur through a kind of photographic process, in which “pictures” of degradation or excellence impressed themselves onto the physical form of the developing child in the womb.

This placed the weight of inheritance onto the mother, and the father lost an active role, except as a mechanical catalyst of reproduction, or as a possible source of degradation. The best role he could play was to place himself entirely at the service of his mate, making her as comfortable and pleasant as possible.

Making an Impression on the Mother

The imposition of a man’s lust for a woman was crystallized in the form of the traditional marriage institution, in which the woman had little or no legal rights to refuse sexual intercourse with her husband. She had little legal status except as the chattel of her father and then, after marriage, of her husband. The traditional arrangement was wrong, it was said, not just because of the deprivation of the individual rights of the woman, but because this deprivation caused the biological degradation of their offspring. The children of women whose partners had forced sexual intercourse on them, were liable to be formed in the womb as physically defective because they were “impressed” by the repulsion felt by the woman for her partner and by her feelings that the child was unwanted.

Conceived in Disgust and Brought Forth in Agony

Was the sexual act the result of love and affection or the result of “lust”—the “bestial” and degrading impulse associated with the male? Sex that was in accord with the natural promptings of love would result in superior offspring; sex that was not in accord with feelings of love, but was sanctioned by a “base” contract—in which sex was offered or taken in return for money or material security—would result in inferior offspring. The traditional institution of marriage was therefore literally degrading the human race because it prohibited people from following their natural sexual attractions (outside the marriage partnership), and it sanctioned forced sex within marriage, no matter whether the woman found her partner attractive or not.

Spiritualists, inclined to regard the realm of the spirit as co-equal with (if not superior to) the material world, came to believe that all children were “immaculate conceptions.” They were the result of an initial spirit implant, that guided the process of becoming flesh. Embryonic development, however, was thought to be almost always “downward” from there, corrupted by impressions from the outside world, as mediated through the mother.

Spiritualist poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox, “My Creed,” in words that may or may not be merely metaphorical, put it this way:

Whoever was begotten by pure love

And came desired and welcomed into life,

Is of immaculate conception. He

Whose heart is full of tenderness and truth,

Who loves mankind more than he loves himself,

And cannot find room in his heart for hate,

May be another Christ. We all may be

The Saviors of the world if we believe

In the divinity which dwells in us

And worship it, and nail our grosser selves,

Our tempers, greeds, and unworthy aims

Upon the cross. Who giveth love to all,

Pays kindness for unkindness, smiles for frowns,

And lends new courage to each fainting heart

And strengthens hope and scatters joy abroad.

The special spiritualist twist on this was the belief that women, through developing themselves as spirit mediums, could bring elevated spirits into the womb, replacing worldly influences onto the fetus, with spiritual ones, distillates of the highest characteristics of the race, thus perfecting the child. The spirit influence would overpower the physical facts of coition—even making it irrelevant to the biological issue whom the woman had sex with (or with how many men).

Woman would help reclothe the spirits of the past in material, human form, making possible the resurrection of the dead and the communion of saints, the past and the present generation working together to create the future in the form of the new race. The spirits had come, in a millennial outpouring, to elevate the racial pool, and counter downward pressures that had tended to degrade humans. They would regenerate humans, as they had first been created. Worldly institutions and practices that oppressed women or that allowed lower, bestial male influences to dominate women, were responsible for the degradation of the race and had to be overcome.

2. A Nobler Race

The drive to reform the marriage relation and to empower women was not merely a movement to give them the individual rights naturally due to them. It was also a purity movement, meant to give them the power to ward off all impositions on their person that would degrade their offspring.

The spiritualist model of genetic inheritance led in contrary directions—one was to argue for more sexual freedom; for the individual’s right to make sexual choices; for more power for women to make their own decisions about maternity. However, it also led to measures to rationalize and control and direct sexual reproduction—to birth control, but also to the idea that women had to be closeted against even psychic and mental and emotional upset (to protect fetuses), and they had to be passive during gestation, and open themselves only to the “elevated” and spiritual.

Some progressives also came to the conclusion that those who were “unfit” to breed, or who were inferior in some way, had to be discouraged—or prevented—from reproducing.

After the Civil War, as whites were feeling “race pressure” from an increasing population of free blacks and non-English immigrants, a part (not all) of the progressive movement directed its eforts at preserving and guarding racial purity. In this intellectual atmosphere (what was later called) “eugenics” was born. Spiritualists believed that at the most powerful moments of the sexual act, the noblest spirits of the dead could be deliberately invoked and invited back to earth in an embodied form by imprinting their spirits into the womb. The mother’s womb, it was said, was the gate through which the destiny of humankind would pass. She was the medium for that Future. When the spirits of the past re-entered the world through that narrow gate, and mixed with humans in this way, they would elevate the race, which had degenerated from its original purity.

This was the millennium that was about to be ushered in by “Free Love,” which is to say, sexual relations governed exclusively by feelings of love, in which partners who conceived of themselves as one another’s “spiritual affinities” would breed a higher order of human. Some white liberals and progressives—even some of those who had been leaders in the Abolitionist movement—developed ideas, just before and after the Civil War, influenced by Social Darwinism, that were meant to place racial hierarchies on a scientific basis, and elevate white racial and cultural characteristics as the purest approximation to heaven.

This was the millennium that was about to be ushered in by “Free Love,” which is to say, sexual relations governed exclusively by feelings of love, in which partners who conceived of themselves as one another’s “spiritual affinities” would breed a higher order of human. Some white liberals and progressives—even some of those who had been leaders in the Abolitionist movement—developed ideas, just before and after the Civil War, influenced by Social Darwinism, that were meant to place racial hierarchies on a scientific basis, and elevate white racial and cultural characteristics as the purest approximation to heaven.

Abolitionist lawyer, visionary, and spiritualist Stephen Pearl Andrews envisioned a new organization, which he called “The Pantarchy,” as a corps of free love experimenters and activists, who would regenerate the human race through “breeding on a scientific basis.” He found much to admire in the sexual arrangments instituted in the utopian Perfectionist communities (at Poultney, Vermont, and then at Oneida, New York) founded by John Humphrey Noyes, where all adults were married to all others, but where mating for the purpose of the reproduction of offspring was “scientifically” regulated by Noyes and a small committee of elders. Not surprisingly, when surveying the human race in order to find the highest physical and mental specimens for the “Pantarchy,” Andrews came to the conclusion that he himself embodied an unparalleled example of one who should sire the Coming Race.

Those who were not on such an exalted level, he supposed, should be discouraged or prevented, in as kind a way as possible, from breeding. Eventually, their influence would disappear from the racial pool.

What were the “scientific” racial distinctions of inferiority and superiority, upon which decisions about breeding would be made? Andrews cited the work of James W. Redfield as an outline for this “science.” Here are two pages from Redfield’s Comparative Physiognomy; or Resemblances between Men and Animals, which he self-published in 1852, that provide an illustration of his methodology and results:

Abolitionist, radical reformer, and nationally-known spiritualist, Warren Chase, lectured toward the end of the Civil War, on the way in which the end of Slavery would reduce the “unnatural” practice of miscegenation and ultimately result in the segregation of the races and the “natural” migration of blacks to the Tropics and their disappearance from the Temperate Zone, which was the natural homeland of the more intelligent and advanced white race.

The fear of racial mixing—with its supposed result in the degeneration of the race—led radical spiritualists to promote measures to maintain and fortify “blood purity,” and prevent contaminating the blood or mixing it with things that would bring down the human type. Many radical spiritualists, intent on directing human evolution toward the spiritual and away from the “bestial,” were active leaders in the opposition to mandatory smallpox vaccination, partly because vaccination involved the injection of blood products into humans, resulting in the “promiscuous” mixing of blood. Especially repugnant for those who believed that mixing the blood meant changing the genetic inheritance was the idea of injecting bovine blood products—weakened or killed cowpox grown in a cow’s bloodstream—into humans, the standard method of producing and administering vaccine against smallpox.

The fear of racial mixing—with its supposed result in the degeneration of the race—led radical spiritualists to promote measures to maintain and fortify “blood purity,” and prevent contaminating the blood or mixing it with things that would bring down the human type. Many radical spiritualists, intent on directing human evolution toward the spiritual and away from the “bestial,” were active leaders in the opposition to mandatory smallpox vaccination, partly because vaccination involved the injection of blood products into humans, resulting in the “promiscuous” mixing of blood. Especially repugnant for those who believed that mixing the blood meant changing the genetic inheritance was the idea of injecting bovine blood products—weakened or killed cowpox grown in a cow’s bloodstream—into humans, the standard method of producing and administering vaccine against smallpox.

Another theory also contributed to the mix. It was an expression of the Romantic idea that the ways of the natural world—including “primitive” human faculties, such as emotion and feeling, expressed subjectively in the individual—constituted a guide to human behavior superior to the dictates of human logic, reason, or cultural or religious tradition or convention. It drew from Protestant and Revolutionary rejection of traditional authority, as well as the writings of Rousseau and Kant. It was mediated through utopian reformers, who took this and first made it anarchistic, holding the feelings and impulses of the individual to be the sovereign authority over his or her own behavior.

Thus, they believed that sexual relations were entirely the concern of the individuals involved. No one else—neither individually nor collectively—had any right to intrude or criticise. The “natural” feeling of sexual attraction had a physical, even chemical, basis—and what could be wrong with what were natural, physical processes?

It was this Romantic idea of sexuality—natural and free of any “priestly” judgment and answerable only to individual “monitions”—that was celebrated in Goethe’s novel, Elective Affinities, in which the constraints of traditional marriage are regarded as artificial and oppressive, and the individuals’ own sexual attractions to their sexual “affinities” are regarded as authoritative.

The same utopian reformers, however, could pass, almost without thinking, from radical individualism to radical socialism—holding that retrogressive traditional and conventional distinctions between people should be eliminated, and that the State should allow no individual to make even sexual decisions that might impede the largest good. Free Love and socialism traveled together through the utopian communities of 19th-century America. Socialism, even into the 20th century, embraced Free Love, because it was a way to eliminate the recalcitrant units of society—that is, nuclear families—that would impede socialist (or communist) economic organization. By that time, its virtues were not its supposed basis in radical individualism, but rather in its role in eliminating the (reactionary) individualism of patriarchal, pre-communist societies in favor of State control of reproduction.

French Utopian Socialist Charles Fourier had used the notion of “affinities” as the basis for his idea to re-order society by eliminating the traditional marriage institution and thus allowing and encouraging the natural operation of “passional affinities,” who would then conduct their sexual activities solely on the basis of sexual attraction.

Charles Fourier on Passion (at The History Guide)

So how did the reduction of sexuality to a material and supposedly scientific basis tie Free Love to spiritualism? One way to explain it is simply to say that, to spiritualists, the material world bodied forth the spiritual. Angels walked the streets of Boston, tipping tables, speaking through little girls, taking shape, turning all material forms, through a kind of sacred alchemy of analogy, into emblems of heaven. Angelic society, which had now come to Earth, and which was now infusing the mundane, had no need of external, “artificial” laws or practices—including marriage—whose only function, under the new dispensation, was to enchain free spirits. Marriage, therefore, was almost always oppressive to those who were bound by it. Andrew Jackson Davis was only the best known spiritualist who espoused the idea of elective or innate affinities—that is, specific to the individuals and not dependent on external authority, which was inevitably coercive and repressive.

John Humphrey Noyes on Free Love

The most renowned students and exponents of Fourier’s ideas in America, Albert Brisbane and Marx Lazarus, were both spiritualists, as were Stephen Pearl Andrews and Josiah Warren, the founders of Modern Times, a notorious Free Love community on Long Island. The writers of works on “sexual hygiene” sought purity in the sexual relations, and this would be achieved, according to the radicals, by sexuality that was ordered around the attractions of affinities. Orson Fowler, Marx Lazarus, and others, wrote guidebooks on physiology that advocated the re-ordering of sexual relations.

Thomas and Mary Nichols wrote Marriage, which equated marriage with slavery, and Mary published a novel, Mary Lyndon, which sympathetically portrayed its heroine advancing beyond an oppressive traditional marriage into Free Love and spiritualism. The Nichols’, residents for a while at Modern Times, set up a short-lived free love community in Yellow Springs, Ohio, named Memnonia.

Stephen Pearl Andrews, Horace Greeley, and Henry James. Love, Marriage, and Divorce, and the Sovereignty of the Individual. New York: Stringer & Townsend, 1853.

Albert Brisbane. Theory of the Functions of the Human Passions; followed by an outline view of the fundamental principles of Fourier’s theory of social science. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1856.

Marx Edgeworth Lazarus. Love vs. Marriage (New York: Fowlers & Wells, 1852).

Marx Edgeworth Lazarus. Passional Hygiene and Natural Medicine; embracing the harmonies of man and his planet. New York: Fowlers & Wells, 1852.

Orson Squire Fowler. Love and Parentage, Applied to the Improvement of Offspring: Including Important Directions and Suggestions to Lovers and the Married Concerning the Strongest Ties and the Most Sacred and Momentous Relations (Wortley: J. Barker, 1844).

Mary S. Gove Nichols. Mary Lyndon; or, Revelations of a Life; an Autobiography. New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1855.

Thomas Low and Mary S. Gove Nichols. Marriage: Its history, character, and results. Cincinnati: V. Nicholson & Co., 1854.

Thomas Low Nichols. Esoteric Anthropology (the mysteries of man): a comprehensive and confidential treatise on the structure, functions, passional attractions, and perversions, true and false physical and social conditions, and the most intimate relations of men and women. New York: The Author, 1853.

After Modern Times folded, Andrews, Brisbane, Lazarus, and others attempted to create an urban Free Love association in New York City in 1854-55, and then after setbacks, a Free Love commune in 1857-58.

During this time, spiritualists brought the doctrines of free love forward in public in a series of conventions—two at the Free Love community at Berlin Heights, Ohio, in 1856 and 1857, one at Buffalo, New York in 1856, one at Ravenna, Ohio in 1857, and, three during its culminating “summer of love” in 1858, the first at Rutland, Vermont, the second at Utica, New York, and the third at Kiantone, in Chautauqua County in Western New York (see Spiritualist Listings page for links to reporting on Rutland, Utica, and more on the Free Love League).

The notoriety that Free Love spiritualists gained during these conventions put a damper on the Free Love movement for a time. Also, radical individualism—key to the first wave of the Free Love Movement—was overshadowed before and during the Civil War, in favor of social “union” and unity, and not toward ideas that justified “secession,” either from the national or the marriage union. As a result, Free Love went underground within spiritualism until after the War, when it culminated in events that swirled around Victoria Woodhull and the American Association of Spiritualists.

3. Free Love Furor

Victoria Claflin Woodhull burst on the spiritualist community in 1871. For spiritualists, she was the embodiment of the issue of “free love,” a doctrine whose association with spiritualism reached its most intimate, yet public, point with her.

Two persons, a male and a female, meet, and are drawn together by a mutual attraction-a natural feeling unconsciously arising within their natures of which neither has any control-which is denominated love. This a matter that concerns these two, and no other living soul has any human right to say aye, yes or no, since it is a matter in which none except the two have any right to be involved, and from which it is the duty of these two to exclude every other person, since no one can love for another or determine why another loves.

If true, mutual, natural attraction be sufficiently strong to be the dominant power, them it decides marriage; and if it be so decided, no law which may be in force can any more prevent the union than a human law could prevent the transformation of water into vapor, or the confluence of two streams; and for precisely the same reasons: that it is a natural law which is obeyed; which law is as high above human law as perfection is high above imperfection. They marry and obey this higher law than man can make-a law as old as the universe and as immortal as the elements, and for which there is no substitute.

They are sexually united, to be which is to be married by nature, and to be thus married is to be united by God. This marriage is performed without special mental volition upon the part of either, although the intellect may approve what the affections determine; thus is to say, they marry because they love, and they love because they can neither prevent nor assist it. Suppose after this marriage has continued an indefinite time, the unity between them departs, could they any more prevent it than they can prevent the love? It came without their bidding, may it not also go without their bidding? And if it go, does not the marriage cease, and should any third persons or parties, either as individuals or government, attempt to compel the continuance of a unity wherein none of the elements of the union remain?

—Victoria C. Woodhull, “‘And the Truth Shall Make You Free,’ a Speech on the Principles of Social Freedom, Delivered in Steinway Hall, Monday, Nov. 20, 1871” (New York: Woodhull & Claflin, 1871): 15

Picture of Victoria C. Woodhull

Woodhull had made a name for herself as an outspoken advocate for women’s rights, especially for women’s right to decide for themselves—without reference to, or permission from, the strictures of Church or State—their sexual relations, and, in particular, when and with whom “to assume the maternal role.” She was also a proponent of a radical reform of the government of the United States, in line with Socialist ideals. Her newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, was the first publisher in the United States of Marx and Engel’s Communist Manifesto.

We mean treason; we mean secession, and on a thousand times grander scale than was that of the South. We are plotting revolution; we will overslough this bogus republic and plant a government of righteousness in its stead, which shall not only profess to derive its power from the consent of the governed, but shall do so in reality.

—“A Lecture on Constitutional Equality, Delivered at Lincoln Hall, Washington, D. C., Thursday, February 16, 1871, by Victoria C. Woodhull.” (New York: Journeymen Printer’s Coop Assn, 1871)

As she had prepared to declare herself a candidate from the “Equal Rights Party” for the U.S. Presidency, she attended the 1871 annual convention in Troy, New York, of the American Association of Spiritualists, an organization in which she had never before held office—or even been a member of. The day before the Convention, her friends distributed to all the delegates reprint copies of a long article from the New York Golden Age, just written by women’s rights advocate Theodore Tilton. It was a glowing biographical sketch of Woodhull that described her as a spiritualist medium who was blessed with a spirit-guide, the spirit of Greek orator Demosthenes.

As she had prepared to declare herself a candidate from the “Equal Rights Party” for the U.S. Presidency, she attended the 1871 annual convention in Troy, New York, of the American Association of Spiritualists, an organization in which she had never before held office—or even been a member of. The day before the Convention, her friends distributed to all the delegates reprint copies of a long article from the New York Golden Age, just written by women’s rights advocate Theodore Tilton. It was a glowing biographical sketch of Woodhull that described her as a spiritualist medium who was blessed with a spirit-guide, the spirit of Greek orator Demosthenes.

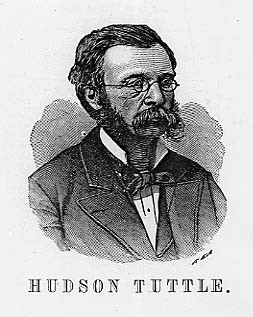

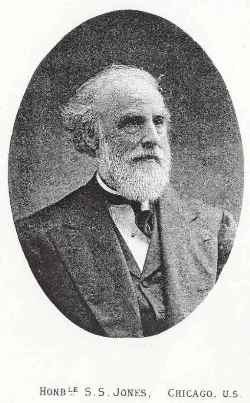

She took the convention by storm and was voted its President, much to the disappointment of the large faction of spiritualists in the organization who were vehemently opposed to “free love,” which they believed—as it was preached and practiced by Woodhull—to be equivalent to sexual licentiousness, though disguised as a doctrine of sexual purity. Eventually these spiritualists found as spokespersons spiritualist mediums and lecturers Hudson Tuttle and Emma Hardinge Britten. Leading the editorial opposition against Woodhull in the spiritualist press was Stevens Sanborn Jones, editor of the Chicago-based Religio-Philosophical Journal.

[. . .] The Troy Convention was used as the means whereby to prostitute Spiritualism to the support of unparalleled selfishness, and when Mrs. Woodhull said in her speech of acceptance, the spirits had foretold her election, she revealed the key to the black abyss of fraud and deception by which that event had been accomplished.

I would not narrow the sphere of Spiritualism, rather would I broaden it. It is a slave to no party or issue, but accepts the truths of all. The grand flood of angel manifestations has not for its sole aim to give the ballot to woman, or to make Mrs. Woodhull President of the United States of the World, nor to make men temperate, or to free the slave, or to break down the churches. But there are those who magnify their own views until they conceal the heavens, and believe their petty scheme the sole object for which Spiritualism has dawned on the world.

To such, the great cause in its completeness, says: “Not for one, but for all. I love the church, whose pillars are hoary with age, as well as the newest ‘ism.’ Mine is not impartial devotion to one, but to mold the truths of all into perfect order and completeness, and eliminate their errors.”

Because a huckster consults his guardian-spirit about gardening, does not prove Spiritualism is ordained especially to teach the best methods of dealing with manures and the offal-heap. The restriction and “manuring of its spheres,” exists with the individual who wishes such unwarrantable claims—not with the cause.

—Hudson Tuttle, “American Association of Spiritualists—The New Disgrace,” Religio-Philosophical Journal (Chicago), February 17, 1872.

The next American Association of Spiritualists’ meeting was held in the spring of 1872, at Steinway Hall, in New York City, Woodhull’s home. In her keynote address, Woodhull, as she later put it, was forcefully entranced by the spirit of Theodore Parker and declared that popular, liberal clergyman Henry Ward Beecher was having an extramarital affair with Elizabeth Tilton, a member of his Brooklyn congregation and the wife of Theodore Tilton (the author of the fulsome biographical pamphlet about Woodhull). She repeated the charge in Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. She was successfully prosecuted and jailed for distributing obscene materials through the mail as a result. The charge she leveled against Beecher was only that of hypocrisy: She found nothing amiss, she said, in the fact that such a large-minded and energetic person as Beecher would require more than one sexual partner. What she objected to was Beecher’s being unwilling to admit to it, and being not merely neutral about Woodhull’s free love doctrine (she had hoped for his support), but publicly hostile to it. So, she “outed” him, as some might say today.

The next American Association of Spiritualists’ meeting was held in the spring of 1872, at Steinway Hall, in New York City, Woodhull’s home. In her keynote address, Woodhull, as she later put it, was forcefully entranced by the spirit of Theodore Parker and declared that popular, liberal clergyman Henry Ward Beecher was having an extramarital affair with Elizabeth Tilton, a member of his Brooklyn congregation and the wife of Theodore Tilton (the author of the fulsome biographical pamphlet about Woodhull). She repeated the charge in Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. She was successfully prosecuted and jailed for distributing obscene materials through the mail as a result. The charge she leveled against Beecher was only that of hypocrisy: She found nothing amiss, she said, in the fact that such a large-minded and energetic person as Beecher would require more than one sexual partner. What she objected to was Beecher’s being unwilling to admit to it, and being not merely neutral about Woodhull’s free love doctrine (she had hoped for his support), but publicly hostile to it. So, she “outed” him, as some might say today.

On the question of Woman’s Rights, I here have nothing to say, for it is not the real issue. They, who have closely followed the progress of this movement which with stealthy step and crafty turning, has gone forward, ever presenting its Pecksniffian countenance of sham virtue and blushing modesty, understand that beneath the cant for a pure and incorruptible government lies a stratum of selfishness and ambition, blacker than that of revolting Satan. The people at large know little of the Internationals, but enough, if Mrs. W. rightly interprets them. If the scheme of government she proposes be inaugurated, well is it premised in the “call:” “This reformation, properly begun, will expand into a political revolution which shall sweep over the country,” etc: and that “revolution” necessarily will be one of blood.

—Hudson Tuttle, “The Steinway Hall Convention,” Religio-Philosophical Journal, May 25, 1872.

Her followers saw her as a martyr, severely oppressed, and saw her brief imprisonment as a violation of her right of free speech.

Woodhull advocated individual sovereignty as a means to free women of imposition on their reproductive faculties. Making sure that sexual activity would be determined by the woman and only on the basis of her affections—not by the man’s lust or on the basis of a “contract”—would insure that the human race would be elevated and made more spiritual.

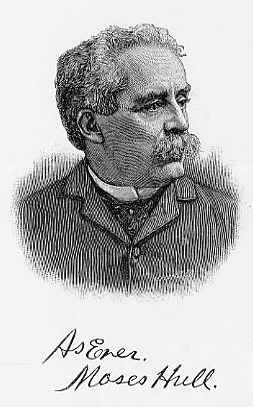

Hull wrote about his experiences and convictions, convinced they were in line with Woodhull’s. Later, he wrote that his letter was an attempt to draw fire “away from a noble lady,” although she didn’t seem to notice at the time that it was at all different from what she believed, but rather regarded it as an example of freedom and honesty.

Hull wrote about his experiences and convictions, convinced they were in line with Woodhull’s. Later, he wrote that his letter was an attempt to draw fire “away from a noble lady,” although she didn’t seem to notice at the time that it was at all different from what she believed, but rather regarded it as an example of freedom and honesty. The London Post announces the approaching marriage of Mrs. Victoria C. Woodhull to “the scion of a noble house.” With that jealous regard for her reputation which has always distinguished her, Mrs. Woodhull takes advantage of the occasion publicly to proclaim her abhorrence of the sect of free lovers, and to declare that during no part of her life did she favor free love, even tacitly. She further explains that the articles which appeared over her signature, advocating the detestable doctrines of the sect, were not written by her at all, and her name was appended to them without her authority and during her absence. It is evident from this that society has been misled concerning Mrs. Woodhull. It would not or could not penetrate the clouds of obloquy that hung heavily along the horizon of her vestal virtues. She has been pursued by a public sentiment that judged her without cause and condemned her without reason. Now, upon the eve of her marriage to “the scion of a noble house,” she rends the vail of detraction, and stands revealed as pure and lustrous as an electric light in an alabaster vase.

The London Post announces the approaching marriage of Mrs. Victoria C. Woodhull to “the scion of a noble house.” With that jealous regard for her reputation which has always distinguished her, Mrs. Woodhull takes advantage of the occasion publicly to proclaim her abhorrence of the sect of free lovers, and to declare that during no part of her life did she favor free love, even tacitly. She further explains that the articles which appeared over her signature, advocating the detestable doctrines of the sect, were not written by her at all, and her name was appended to them without her authority and during her absence. It is evident from this that society has been misled concerning Mrs. Woodhull. It would not or could not penetrate the clouds of obloquy that hung heavily along the horizon of her vestal virtues. She has been pursued by a public sentiment that judged her without cause and condemned her without reason. Now, upon the eve of her marriage to “the scion of a noble house,” she rends the vail of detraction, and stands revealed as pure and lustrous as an electric light in an alabaster vase.